SPUR (2024) 8 (1): https://doi.org/10.18833/spur/8/1/2

Undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry (URSCI) experiences are found to enhance student growth in skill development. Previous research has not established what literature exists on intentionally preparing students for work through URSCI experiences in the United States. A scoping review was conducted to systematically map what the literature reveals that faculty, programs, and institutions are intentionally providing with URSCI experiences. Five databases and Google Scholar were searched. Data were charted by characteristics tied to the research question. The results demonstrated a need for research on URSCI to intentionally and directly assess how undergraduate research can be used as a tool for career readiness. The current reliance on the implicit aspects of the URSCI experience to develop career readiness competencies is not a sufficient approach.

Recommended Citation: MacDonald, Amanda B., Jeanne Mekolichick, Eric E. Hall, Kristin Picardo, Rosalie Richards 2024. Scoping Review: Literature on Undergraduate Research and Career Readiness. Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 8 (1): 3-14. https://doi.org/10.18833/spur/8/1/2

In recent years, the national narrative on the value of higher education has shifted. Americans are losing faith in an undergraduate degree and its worth as a vehicle for social mobility and a public good. Gallup poll data from 2015 shows that 57 percent of respondents indicated they had a “great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in higher education, compared to 48 percent in 2018 and 36 percent in 2023 (Jones 2024). Employers in the United States also are losing confidence in the value of a undergraduate degree. The 2021 report, “How College Contributes to Workforce Success,ˮ commissioned by the American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), shows a decrease in employer confidence in higher education dropping from 49 percent in 2018 to 41 percent in 2020 (Finley 2021). Given these data points, the value of higher education is unclear to a growing group of the public and employers.

With an eye on these trends, in 2019 the Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR) released a white paper, “Undergraduate Research: A Road Map for Meeting Future National Needs and Competing in a World of Change” (Altman et al. 2019) that argued for undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry (URSCI) experiences as a powerful tool for achieving workforce needs. The authors here use both the more inclusive phrase “undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry” reflective of the breadth of scholarly and creative activities across disciplines, as well as the more truncated “undergraduate research” more commonly found in the literature. The concise phrase, undergraduate research, is meant to be inclusive of scholarly and creative endeavors as well.

Supporting this position, another data point from the 2021 AAC&U’s How College Contributes to Workforce Success report (Finley 2021) shares that 85 percent of employers surveyed were more likely or somewhat more likely to consider hiring a candidate who had a mentored research experience. Considering these documents together begs the question: What elements of the URSCI experience contribute to workplace readiness and are recognized by prospective employers?

The National Association of Colleges and Employers’ (NACE) annual job outlook survey collects information on the skills employers seek in new undergraduates. Using these data, in 2021 NACE updated their list of career readiness competencies that students need to enter and thrive in today’s work environment. Eight competencies emerged: critical thinking, teamwork, communication, professionalism, career and self-development, leadership, technology, and equity and inclusion (NACE 2024). These competencies represent demonstrated outcomes of student participation in URSCI experiences. Mekolichick (2021) articulates the alignment in a NACE Journal article to assist career center professionals in highlighting the value of undergraduate research (UR) experiences for the workplace. Mekolichick (2023) later elucidates this in the 2023 CUR position paper, “Recognizing Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Inquiry as a Career-Readiness Tool,” aimed at helping faculty intentionally identify these competencies for themselves and their students.

Specifically, URSCI experiences are found to enhance student learning, including growth in communication skills, critical thinking and teamwork, a greater understanding of the research process, technical skills, and data analysis competencies (see, for example, Brownell and Swaner 2010; Lopatto 2004; Osborn and Karukstis 2009). In addition, the literature consistently reports student improvement in related dispositions and social psychological constructs, including confidence, ability to work independently and overcome obstacles, increases in self-efficacy, cultivation of a professional identity, clarification of career path, leadership, and professionalism (see, for example, Hunter, Laursen, and Seymour 2007; Osborn and Karukstis 2009; Seymour et al. 2004). In sum, research clearly demonstrates the overlap between the benefits of URSCI and the career readiness competencies identified by employers. However, given public sentiment on the ability of higher education to achieve workforce needs, there is a disconnect between the documented career readiness skills gained in URSCI experiences and the translation of these experiences to the world of work.

CUR recognized this gap and charged a board working group (2021–2023) to advance this work. At the conclusion of their work in 2023, an implementation work group on undergraduate research and career readiness was established. As work began, the group recognized a need to learn more about the state of the literature. To date, there has not been a thorough review of the extent to which URSCI experiences have intentionally included career preparation in the United States. Taking into account the value shift regarding higher education and the foundational skills desired by employers described above, a scoping review was conducted to systematically map what the literature reveals about what faculty, programs, and institutions are intentionally providing to successfully bridge this articulation gap. This scoping review aimed to answer the question: What intentional career readiness competency programming are faculty, programs, and higher education institutions delivering and assessing in undergraduate research, scholarship, and creative inquiry experiences to help students become career ready?

Methods

The protocol was drafted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P; Moher et al. 2015) and was published retrospectively at VTechWorks. The research methodology in this review was based on the JBI methodologies for scoping reviews as described in the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris and Munn 2020). This article follows the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al. 2018).

Eligibility

For inclusion in this review, studies needed to contain at least one NACE competency and an associated assessment of the competency. Publication types included peer-reviewed journal articles, books, book chapters, news articles, white papers, and reports that were housed in the databases or Google Scholar. It is important to note that additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were added at the full-text screening stage. See criteria that begin with “During the full-text screening.” Additionally, there were studies excluded during the full-text screening process that conducted assessments of undergraduate research experiences after a program concluded and included a career readiness evaluation but lacked either an intentional career readiness objective or an associated assessment. The aim of this review was not to prove that undergraduate research experiences prepare students to be career ready, but rather to map researched approaches that faculty, programs, and institutions have successfully piloted to bridge the noted articulation gap.

Inclusion criteria included:

- Any undergraduate research program in a higher education context; all two- to four-year accredited institutions, including community colleges and public and private schools

- Undergraduate research, industry-based research, research internships, scholarship, or creative inquiry OR

- Mention of UR as defined by CUR (“a mentored investigation or creative inquiry conducted by undergraduates that seeks to make a scholarly or artistic contribution to knowledge”; CUR 2024) OR

- Formal UR experience that is mentored, describing student researchers as receiving one-on-one training, research experience, or co-creation of knowledge, scholarship, or creative works

- CUREs (course-based undergraduate research experiences) or capstone courses that align with CUR definition of UR

- Career readiness as defined by NACE (“a foundation from which to demonstrate requisite core competencies that broadly prepare the college educated for success in the workplace and lifelong career management”; NACE 2024) OR

- NACE competencies (“career and self-development, communication, critical thinking, equity and inclusion, leadership, professionalism, teamwork, technology”; NACE 2024) OR

- Industry-based research experience, industry internships with research, employment, professional skills, workplace skills, workplace preparation

- UR, scholarship, or creative inquiry in any discipline, conducted within the United States. Publications can be published by an outlet (e.g., journal).

- No date limits.

- During the full-text screening, the primary goal of the study must include a career readiness intervention regarding one or more NACE competencies (whether explicitly named as NACE or not) with an associated assessment or outcome that is described and designed to measure student mastery of the competency or competencies. Language should state the goal of preparing students for the world of work with a NACE competency—whether explicitly named as NACE or not—that includes an intervention and associated assessment designed to measure student mastery of the NACE competency.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Graduate students of graduate school programs. Middle school or high school students. Except if undergraduate research (etc.) programs or initiatives (as defined in Inclusion) also are included and data or descriptions of interest are (or can be) disaggregated.

- Undergraduate courses with research components only (CUREs or capstone courses that align with CUR definition of UR meet inclusion criteria).

- UR programs hosted by companies outside of higher education institutions (e.g., NASA).

- Outside of the 50 United States; territories of the United States are excluded.

- Publication types excluded are conference proceedings, conference abstracts, opinion pieces, editorials, and reports that can only be purchased from associations.

- During the full-text screening, the primary goal of the study does not include a career readiness intervention regarding one or more NACE competencies (whether explicitly named as NACE or not) with an associated assessment or outcome that is described OR the associated assessment or outcome is mentioned but not described. Studies that include surveys or assessments gathering student feedback on how a UR experience prepared them for their career without a career readiness intervention regarding one or more NACE competencies will be excluded.

Sources

A total of 5 databases were searched in December 2023, and Google Scholar was searched in January 2024. Bibliographic databases were selected to be either non–discipline specific or discipline-specific as related to the research question. An education database was selected to account for interventions taking place in higher education institutions, and a business database was included given the relationship of the outcome with career readiness and the world of work. The following databases were searched:

- Academic Search Complete (1980s–)

- Business Search Complete (1980s–)

- Education Research Complete (1865–)

- Scopus (1800s–)

- Web of Science (1900–)

- Google Scholar (first 204 results)

Search

The search strategy was developed by a librarian on the team, with testing and revisions developed from team discussions. The final search strategy was peer reviewed following the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) 2015 Guideline Statement (McGowan et al. 2016) by two librarians outside of this study, both of whom had experience as systematic review coauthors or with evidence synthesis methods. Revisions were made based on their recommendations. The final search strategy used for Scopus was as follows:

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( ( undergrad* ) W/3 ( scholarship OR creativ* OR research* ) ) AND ( nace OR “national association of colleges and employers” OR (( career* OR job OR jobs OR profession* OR work* OR employ* OR occupation* ) W/3 ( readiness OR ready OR development* OR competen* OR skill* OR prepar* ) ) ) )

All searches were conducted utilizing the title, abstract, and author keywords fields within each database. Filters such as language, publication date, or publication type were not used during the search.

Selection

Covidence was the software tool used for the project (Covidence 2023). To initiate the study, pilot assessments were conducted at the start of each stage of the review process (i.e., title and abstract screening, full-text screening, and data extraction). During the title and abstract screening, 50 studies were reviewed for the pilot by the team, and conflicts were discussed and resolved before completing the screening for this stage. During the full-text screening pilot, 25 articles were reviewed. The team noted a high rate of conflicts during the full-text screening pilot, discussed the conflicts, and decided to add additional inclusion and exclusion criteria specifically for this round. To resolve the conflicts, the team repeated the full-text screening stage of the pilot with the revised criteria. During the data extraction stage, key characteristics or pieces of information from the studies were extracted in a structured way. Five studies were screened during the pilot by the team, and conflicts were discussed and resolved before completing the extraction phase. For all stages of the review process, two team members screened each study. All conflicts were discussed and resolved by consensus.

Data

Data were extracted on publication characteristics (reference identification number, journal title, study title, lead author, and year of publication), study characteristics (type of institution, aims/purpose, sample size, and discipline of students), career readiness aspect (NACE competency or skill and associated career readiness intervention), and career readiness assessment (how was it assessed, outcomes of the assessment, and any practices or recommendations the authors wished to share).

Synthesis

During the extraction phase, the team chose the method of copying and pasting relevant information into the form directly from the studies. As a result, there were lengthy responses on the form. Some responses were significantly trimmed during the data cleaning and visualization process to make Table 1 easier to read.

Results

Selection

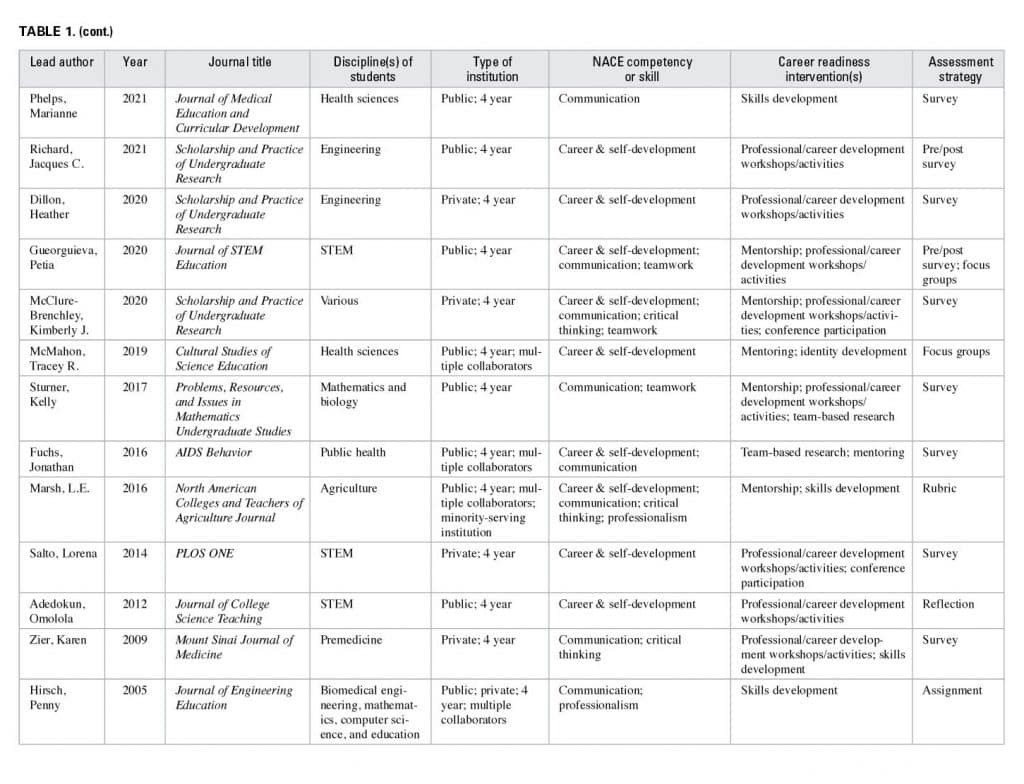

A total of 2518 studies were imported into Covidence. In all, 888 duplicate items were identified by Covidence prior to study selection. Twelve duplicate items were identified and removed manually during the screening processes of the review. The title and abstract screening included 1618 studies, and 1328 studies were excluded. In total, 290 studies were assessed during the full-text screening. The full-text screening excluded 264 studies for the following reasons: 184 did not include a career-readiness intervention with an associated assessment or outcome; 39 were conference proceedings or abstracts, opinion pieces, editorials, or costly reports; 20 took place outside of the United States; 12 were courses with a research paper or project but not a CURE; 6 were research programs for graduate, middle school, or high school students or may have included undergraduate students but data did not differentiate status, and 3 were undergraduate research programs hosted by companies. There were 26 studies remaining that were deemed eligible for this review (see Figure 1).

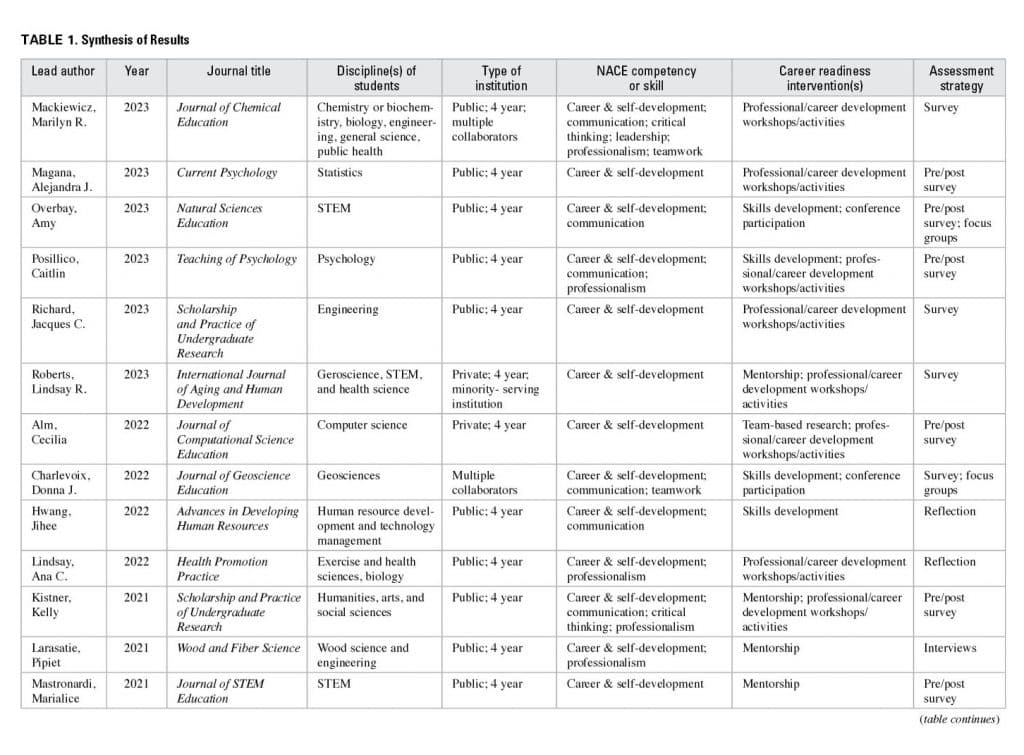

Characteristics

The data extracted and charted for this review are showcased in Table 1. Each study’s lead author, year of publication, journal title, discipline(s) of students, type of institution, NACE competency or skill, career readiness intervention(s), and assessment strategy are displayed. The table has been sorted first by year, newest to oldest, then alphabetically by lead author’s last name, and finally by discipline.

Results

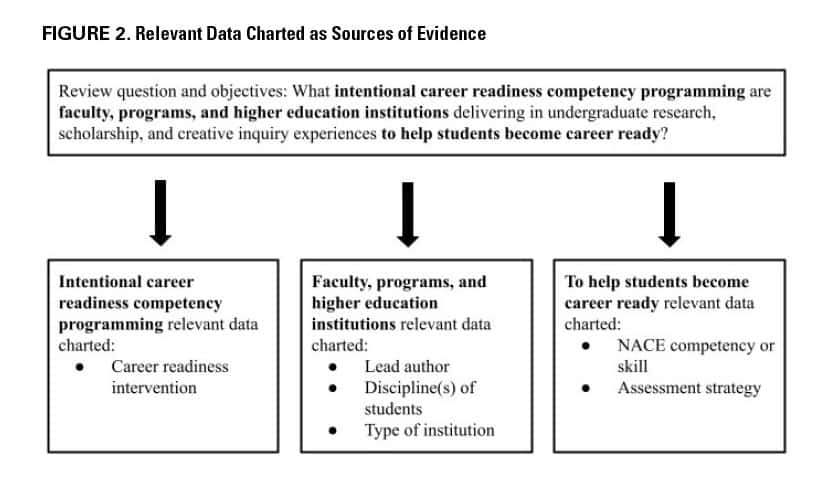

For this scoping review 26 articles were identified that met all the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). Figure 2 displays the relevant data charted for each part of the review question and objectives. For example, regarding the “intentional career readiness competency” portion of the research question, the career readiness interview was extracted from each study for data charting (see Figure 2).

Description

Eighteen of the 26 articles identified were published since 2020, suggesting that the focus on career readiness is a recent phenomenon. The primary journals that have published this work are the Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research (n = 5) and the Journal of STEM Education (n = 2). The remaining publications were single articles from a variety of journals. Approximately 81 percent of articles focused on traditional STEM disciplines. Nineteen of the studies occurred primarily at four-year public institutions.

Of the 26 studies evaluated, 21 focused on career and self-development, and 13 targeted communication. Professionalism (n = 6), teamwork (n = 5), and critical thinking (n = 4) comprised the next frequency level of competencies addressed. The competencies least addressed were leadership (n = 1), technology (n = 0), and equity and inclusion (n = 0). Interventions implemented for the purpose of developing career competencies were primarily professional or career development workshops and activities (n = 16), followed by mentorship (n = 10) and skills development (n = 8). Unique interventions included conference participation (n = 4) and team-based research (n = 3). One study used an identity development intervention. When examining assessment methods, surveys (n = 24) were the primary mechanism for gathering data. However, a few studies employed focus groups (n = 4) and reflective assignments (n = 3), with single studies using interviews, assignments, or rubrics.

Discussion

Summary

Of the 26 studies examined, the majority described competency outcomes at large four-year public institutions. Only five represented private institutions with a few (three) partnering with public universities. Only 8 percent of the studies identified minority-serving institutions as partners (Marsh et al. 2016; Roberts et al. 2023). Not surprisingly, approximately 85 percent of the studies reported engagement in recognized STEM disciplines, offering large scope for non-STEM disciplines to assess career readiness resulting from research and creative inquiry.

Evidence clearly demonstrates that among the commonly addressed NACE competencies, research programs have focused primarily on developing career and self-development competency (n = 21) to help students consider how their research experiences can support their future goals. However, critical competencies such as communication skills (n = 13), professionalism (n = 6), teamwork (n = 5), and critical thinking (n = 4) lag significantly.

Although there has been almost no intentional focus on leadership (n = 1), technology (n = 0), or equity and inclusion (n = 0), most of the examined studies measured growth of only one or possibly two competencies. Since development of different competencies may not be mutually exclusive, a more holistic approach may be warranted. It will be important for future studies and interventions to carefully consider how to specifically integrate, build, and evaluate growth of multiple career readiness skills, such as those reported by McClure-Brenchley, Picardo, and Overton-Healy (2020) and Mackiewicz et al. (2023).

The most common interventions involved professional or career development workshops, seminars, and related activities as supplementary components to the undergraduate research experience. These often took the form of consultations on how to prepare for graduate school or other forms of career exploration (e.g., Magana et al. 2023) and opportunities for students to build their professional networks (e.g., Adedokun et al. 2012). Intentional mentoring for career clarification was ranked as the second-most frequent intervention. The finding regarding mentoring for career development was not surprising, as research indicates that high-quality mentoring results in the greatest gains for both student and mentor (Shanahan et al. 2015; Vandermaas-Peeler, Miller, and Moore 2018). Mekolichick (2023) noted how “mentors can infuse the associated sample behaviors within their undergraduate research, scholarship and creative inquiry projects in visible, transparent, and consumable ways for our students to recognize the relevancy, value and leave with the language and ability to tell their URSCI stories” (1). In addition, the salient practices framework of undergraduate research mentoring (Shanahan et al. 2015) provides a useful scaffolding for mentors as they help build students’ career competencies. This framework identifies practices that align well with NACE competencies. For example, dissemination of research results aligns with communication, and building a community of scholars aligns with teamwork. The third most common interventions targeted skill development, which often focused on building communication skills (e.g., Charlevoix et al. 2022). A unique intervention approach was improvisation workshops (Phelps et al. 2021). Whatever the type of intervention or skill, what was clear from these studies was the need for research programs to collaborate with faculty and staff who have the expertise to build career readiness competencies.

An overwhelming majority of the studies used a self-reporting survey to assess gains in competencies. Often surveys were created for the study or were a modified version of other surveys, including EvaluateUR (Grinberg and Singer 2021), the Undergraduate Research Student Self-Assessment (URSSA; Ethnography and Evaluation Research 2009; Weston and Laursen 2015), and the Survey of Undergraduate Research Experiences (Lopatto 2004, 2009). As noted, a distinct limitation was that these surveys were not designed to assess gains in several NACE competencies. Rather, most focused on research skills that were linked to competencies such as communication, critical thinking, and career and self-development. Two studies used a mixed-methods approach to assessment, and others employed focus groups, interviews, or other reflections or assignments to demonstrate different competencies. The gap in holistic assessment of student career readiness creates a unique opportunity for the design of specific methodologies to assess the roles of UR experiences in advancing the NACE competencies.

Limitations

This scoping review was conducted as part of a Council on Undergraduate Research working group focused on undergraduate research and career readiness. The group concluded that a scoping review would help members better understand the status of career readiness work in UR programs, and where opportunities lie. The research question, objectives, and decisions made aligned with the timeline required by the group. Some forms of gray literature were excluded by eligibility criteria for types of evidence. These included reports that were not included in databases searched but available for purchase at a high cost on association websites; white papers not indexed in the searched databases or Google Scholar; and all conference proceedings, as some proceedings were only published abstracts and the timeline did not allow for contacting authors for the full-text articles. Reference lists of key studies were not scanned for additional items. Hand searching of websites such as NACE and CUR was not conducted. The data charting form was developed to extract information directly related to the research question and also to inform the group’s work in aspects beyond the scope of the research question and objectives. In a future systematic literature review on this topic, researchers should consider crafting broader eligibility criteria and creating a more detailed extraction form to uncover evidence of career readiness competencies that are discussed but not associated with assessments. Use of the NACE competencies and associated assessments is not currently standard in undergraduate research assessment and evaluation practices. Therefore, data charting this type of information was a challenge. At times decisions were made by consensus to exclude articles that appeared to align with the eligibility criteria and potentially valuable to answering the research question, but lacked specificity.

Conclusions

This scoping review demonstrates that there is room to assess and promote the utilization of UR as a tool for career readiness. The recent release of the Mekolichick (2023) position paper should be the impetus for research projects and associated assessments to employ the NACE competencies to measure growth in the career readiness of undergraduate research students. The 2023 call and findings from this study identify the need for urgent action. More intentional, inclusive pedagogies are required to make more transparent the diverse career readiness competencies derived from UR experiences.

Overall, the findings indicate that there is a strong dependence on the URSCI experience itself as a mechanism to develop and sharpen career readiness competencies, without intentionally identifying and assessing specific elements of the URSCI experience that cultivate career readiness competencies in undergraduate students. The current reliance on the URSCI experience without intentional identification and assessment of workplace competencies in an objective way that documents learning is no longer a sufficient approach to best support student success, particularly given the increasing focus on workforce readiness within and beyond the academy. Design and implementation must entail purposeful alignment of the UR experience with desired competency, performance, and behavior outcomes. To the extent that one measures what one values, this gap in assessment of career readiness competencies gained through the URSCI experience calls attention to the lack of focus on their importance. UR leadership is falling short of demonstrating how the URSCI experience contributes to career readiness.

To better serve undergraduate students, more clearly articulate the value of URSCI, and more visibly support community workforce needs, action is called for. Four steps are presented to get started. First, familiarization with the NACE career readiness competencies; choose one competency as a focus for growth in the next URSCI project. Second, identify one learning outcome associated with a UR experience that aligns with the selected competency and review the sample behaviors. Third, make one change to existing project documents, syllabi, student manuals, assignments, etc., that explicitly names the career readiness competency developed. Refer to articles referenced here or the CUR position paper (Mekolichick 2023) for ideas. Finally, using the NACE sample behaviors as a guide, consider developing student and faculty assessments to identify proficiency (NACE 2024). If one competency is already identified and assessed, consider adding additional competencies and sharing the results publicly. The CUR UR as a Career Readiness Tool work group continues, exploring resources and materials needed to support faculty and institutions. Mentors and higher education leaders advancing URSCI are called on to meet this challenge in service to undergraduate students, higher education institutions, and their communities.

Funding

No funding supported this scoping review.

Data Availability

The protocol and associated data, including search strategies, data extraction form, and data exported following the extraction, are available at VTechWorks (https://hdl.handle.net/10919/118669).

Institutional Review Board

IRB was not required for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to C. Cozette Comer and Virginia Pannabecker for providing methodological guidance and feedback throughout this review, peer review of the search strategy, and software training.

References

Adedokun, Omolola A., Dake Zhang, Loran Carleton Parker, Ann Bessenbacher, Amy Childress, and Wilella Daniels Burgess. 2012. “Understanding How Undergraduate Research Experiences Influence Student Aspirations for Research Careers and Graduate Education.” Journal of College Science Teaching 42(1): 82.

Alm, Cecilia O., and Reynold Bailey. 2022. “Scientific Skills, Identity, and Career Aspiration Development from Early Research Experiences in Computer Science.” Journal of Computational Science Education 13(1): 2–16. doi: 10.22369/issn.2153-4136/13/1/1

Altman, Joanne D., Tsu-Ming Chiang, Christian S. Hamann, Huda Makhluf, Virginia Peterson, and Sara E. Orel. 2019. “Undergraduate Research: A Road Map for Meeting Future National Needs and Competing in a World of Change.” CUR White Paper no. 1. Washington, DC: Council on Undergraduate Research.

Aromataris, Edoardo, and Zachary Munn (Eds.). 2020. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI Collaboration. doi: 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01

Brownell, Jayne E., and Lynn E. Swaner. 2010. Five High-Impact Practices: Research on Learning Outcomes, Completion, and Quality. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Charlevoix, Donna J., Aisha R. Morris, Kelsey Russo-Nixon, and Heather Thiry. 2022. “Engaging Two-Year College Students in Geoscience: Summer Pre-REU Internships and Professional Development to Prepare Students for Participation in Research.” Journal of Geoscience Education 70: 323–338. doi: 10.1080/10899995.2021.1977770

Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR). 2024. “What Is CUR’s Definition of Undergraduate Research?” https://www.cur.org/about/what-is-undergraduate-research

Covidence. 2023. “The World’s #1 Systematic Review Tool.” Accessed October 17, 2024. www.covidence.org

Dillon, Heather E. 2020. “Development of a Mentoring Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experience (M-CURE).” Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 3(4): 26–34. doi: 10.18833/spur/3/4/7

Ethnography and Evaluation Research, Research and Innovation Office. 2009. “Evaluation Tools: Undergraduate Research Student Self-Assessment (URSSA).” University of Colorado at Boulder. https://www.colorado.edu/eer/research-areas/undergraduateresearch/evaluation-tools-undergraduate-research-student-self

Finley, Ashley. 2021. How College Contributes to Workforce Success: Employer Views on What Matters Most. Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities.

Fuchs, Jonathan, Aminta Kouyate, Liz Kroboth, and Willi McFarland. 2016. “Growing the Pipeline of Diverse HIV Investigators: The Impact of Mentored Research Experiences to Engage Underrepresented Minority Students.” AIDS and Behavior 20: 249–257. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1392-z

Grinberg, Ilya, and Jill Singer. 2021. “ETAC-ABET and EvaluateUR-CURE: Findings from Combining Two Assessment Approaches as Indicators of Student-Learning Outcomes.” In 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access Proceedings, 37098. ASEE Virtual Annual Conference. doi: 10.18260/1-2–37098

Gueorguieva, Petia, Sayantani Ghosh, Ashlie Martini, and Jennifer Lu. 2020. “MACES Undergraduate Research Fellowship Program: Integrating Research and Education.” Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research 21(2): 42–48.

Hirsch, Penny L., Joan A. W. Linsenmeier, H. David Smith, and Joan M. T. Walker. 2005. “Enhancing Core Competency Learning in an Integrated Summer Research Experience for Bioengineers.” Journal of Engineering Education 94: 391–401. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2005.tb00867.x

Hunter, Anne-Barrie, Sandra L. Laursen, and Elaine Seymour. 2007. “Becoming a Scientist: The Role of Undergraduate Research in Students’ Cognitive, Personal, and Professional Development.” Science Education 91: 36–74. doi: 10.1002/sce.20173

Hwang, Jihee, and Corbin Franklin. 2023. “Course-Based Undergraduate Research in Human Resource Development: A Case Study.” Advances in Developing Human Resources 25: 45–56. doi: 10.1177/15234223221138567

Jones, Jeffrey M. 2024. “U.S. Confidence in Higher Education Now Closely Divided,” Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/646880/confidence-higher-education-closely-divided.aspx.

Kistner, Kelly, Erin M. Sparck, Amy Liu, Hannah Whang Sayson, Marc Levis-Fitzgerald, and Whitney Arnold. 2021. “Academic and Professional Preparedness: Outcomes of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences.” Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 4(4): 3–9. doi: 10.18833/spur/4/4/1

Larasatie, Pipiet, Kathy Young, Arijit Sinha, and Eric Hansen. 2021. “‘A Taste of Graduate School without Really Fully Committing to It’: The Undergraduate Experiential Learning Project at Oregon State University.” Wood and Fiber Science 53: 281–293.

Lindsay, Ana Cristina. 2022. “Avancemos! Building Partnerships between Academia and Underserved Latinx Communities to Address Health Disparities through a Faculty-Mentored Undergraduate Research Program.” Health Promotion Practice 23: 569–576. doi: 10.1177/152483992095

Lopatto, David. 2004. “Survey of Undergraduate Research Experiences (SURE): First Findings.” Cell Biology Education 3: 270–277. doi: 10.1187/cbe.04-07-0045

Lopatto, David. 2007. “Undergraduate Research Experiences Support Science Career Decisions and Active Learning.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 6: 297–306. doi: 10.1187/cbe.07-06-0039

Mackiewicz, Marilyn Rampersad, Kathryn N. Hosbein, Dawn Mason, and Ramya Ajjarapu. 2022. “Integrating Scientific Growth and Professional Development Skills in Research Environments to Aid in the Persistence of Marginalized Students.” Journal of Chemical Education 100: 199–208. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.2c00633

Magana, Alejandra J., Aparajita Jaiswal, Aasakiran Madamanchi, Loran C. Parker, Ellen Gundlach, and Mark D. Ward. 2021. “Characterizing the Psychosocial Effects of Participating in a Year-Long Residential Research-Oriented Learning Community.” Current Psychology 42: 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01612-y

Marsh, L. E., F. M. Hashem, C. P. Cotton, A. L. Allen, B. Min, M. Clarke, and F. Eivazi. 2016. “Research Internships: A Useful Experience for Honing Soft and Disciplinary Skills of Agricultural Majors.” NACTA Journal 60: 379–384.

Mastronardi, Marialice, Maura Borrego, Nathan Choe, and Risa Hartman. 2021. “The Impact of Undergraduate Research Experiences on Participants’ Career Decisions.” Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research 22(2): 75–82.

McClure-Brenchley, Kimberly J., Kristin Picardo, and Julia Overton-Healy. 2020. “Beyond Learning: Leveraging Undergraduate Research into Marketable Workforce Skills.” Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 3(3): 28–35. doi: 10.18833/spur/3/3/10

McGowan, Jessie, Margaret Sampson, Douglas M. Salzwedel, Elise Cogo, Vicki Foerster, and Carol Lefebvre. 2016. “PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 75: 40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

McMahon, Tracey R., Emily R. Griese, and DenYelle Baete Kenyon. 2019. “Cultivating Native American Scientists: An Application of an Indigenous Model to an Undergraduate Research Experience.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 14: 77–110. doi: 10.1007/s11422-017-9850-0

Mekolichick, Jeanne. 2021. “Mapping the Impacts of Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Inquiry Experiences to the NACE Career Readiness Competencies.” NACE Journal. https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/mapping-the-impacts-of-undergraduate-research-scholarshipand-creative-inquiry-experiences-to-the-nace-career-readinesscompetencies

Mekolichick, Jeanne. 2023. “Recognizing Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Inquiry as a Career-Readiness Tool.” Position paper. Washington, DC: Council on Undergraduate Research.

Moher, David, Larissa Shamseer, Mike Clarke, Davina Ghersi, Alessandro Liberati, Mark Petticrew, Paul Shekelle, Lesley A. Stewart, and Prisma-P Group. 2015. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMAP) 2015 Statement.” Systematic Reviews 4: 1–9. https://rdcu.be/dFLtd

National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). 2024. “What Is Career Readiness?” NACE. https://www.naceweb.org/career-readiness/competencies/career-readiness-defined

Osborn, Jeffery M., and Kerry K. Karukstis. 2009. “The Benefits of Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creative Activity.” In Broadening Participation in Undergraduate Research: Fostering Excellence and Enhancing the Impact, ed. M. Boyd and J. Wesemann, 41–53. Washington, DC: Council on Undergraduate Research.

Overbay, Amy, Owen Duckworth, and Joshua L. Heitman. 2023. “The BESST REU: Promoting Soil Science Learning and Shifts in Attitudes toward Science.” Journal of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Education 52: 1–12. doi: 10.1002/nse2.20100

Phelps, Marianne, Catrina White, Lin Xiang, and Hollie I. Swanson. 2021. “Improvisation As a Teaching Tool for Improving Oral Communication Skills in Premedical and Pre-Biomedical Graduate Students.” Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development 8: 1–7. doi: 10.1177/23821205211006411

Posillico, Caitlin, Sarah Stilwell, Jacqueline Quigley, Crystal Carr, Sara Chadwick, Cindy Lustig, and Priti Shah. 2023. “Extending the Reach of the STARs (Students Tackling Advanced Research).” Teaching of Psychology 50: 433–440. doi: 10.1177/0098628321105602

Richard, Jacques C., and So Yoon Yoon. 2021. “Three-Year Study of the Impact of a Research Experience Program in Aerospace Engineering on Undergraduate Students.” Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 4(4): 23–32. doi: 10.18833/spur/4/4/5

Richard, Jacques C., and So Yoon Yoon. 2023. “Impact of Engineering Research Experience Programs on Domestic and International Undergraduate Students.” Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 6(3): 29–47. doi: 10.18833/spur/6/3/6

Roberts, Lindsay R., Criss J. Ririe, Marcella J. Myers, Joshua D. Guggenheimer, and Katherine A. Campbell. 2023. “For Aging Research and Equity: Lessons Learned in Undergraduate Research Education.” International Journal of Aging and Human Development 96: 91–105. doi: 10.1177/00914150221109918

Salto, Lorena M., Matt L. Riggs, Daisy Delgado De Leon, Carlos A. Casiano, and Marino De Leon. 2014. “Underrepresented Minority High School and College Students Report STEM-Pipeline Sustaining Gains after Participating in the Loma Linda University Summer Health Disparities Research Program.” PLOS ONE 9(9): 1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108497

Seymour, Elaine, Anne-Barrie Hunter, Sandra L. Laursen, and Tracee DeAntoni. 2004. “Establishing the Benefits of Research Experiences for Undergraduates: First Findings from a Three-Year Study.” Science Education 88: 493–534. doi: 10.1002/sce.10131

Shanahan, Jenny Olin, Elizabeth Ackley-Holbrook, Eric Hall, Kearsley Stewart, and Helen Walkington. 2015. “Ten Salient Practices of Undergraduate Research Mentors: A Review of the Literature.” Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 23: 359–376. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2015.1126162

Sturner, Kelly K., Pamela Bishop, and Suzanne M. Lenhart. 2017. “Developing Collaboration Skills in Team Undergraduate Research Experiences.” PRIMUS 27: 370–388. doi: 10.1080/10511970.2016.1188432

Tricco, Andrea C., Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, David Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169: 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Vandermaas-Peeler, Maureen, Paul C. Miller, and Jessie L. Moore (Eds.). 2018. Excellence in Mentoring Undergraduate Research. Washington, DC: Council on Undergraduate Research.

Weston, Timothy J., and Sandra L. Laursen. 2015. “The Undergraduate Research Student Self-Assessment (URSSA): Validation for Use in Program Evaluation.” CBE–Life Sciences Education 14(3): ar33. doi: 10.1187/cbe.14-11-0206

Zier, Karen, and Lisa D. Coplit. 2009. “Introducing INSPIRE: A Scholarly Component in Undergraduate Medical Education.” Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine 76: 387–391. doi: 10.1002/msj.20121

Amanda B. MacDonald

Virginia Tech, abmacdon@vt.edu

Amanda B. MacDonald is an associate professor and the undergraduate research services coordinator for university libraries at Virginia Tech. Her work focuses on creating openly accessible resources to support students and faculty engaging with formal undergraduate research experiences. MacDonald coordinates the Advanced Research Skills Program and is deeply involved in the university’s Undergraduate Research Excellence Program. She previously served as the undergraduate research librarian at Louisiana State University.

Jeanne Mekolichick is associate provost of research, faculty success, and strategic initiatives and professor of sociology at Radford University. She provides strategic leadership and direction for the research and creative scholarship enterprise, online education, faculty success, experiential learning, career services, and strategic initiatives. Mekolichick is a workshop facilitator, consultant, and program reviewer. Her work has been funded for mission-central efforts, including inclusive excellence initiatives, community-based research, undergraduate research, and career readiness.

Kristin Picardo is the assistant provost in the Office of Sponsored Programs, professor of biology, and founding director of the Center for Student Research and Creative Work at St. John Fisher University. She has published with undergraduate research students working in her bacteriology lab, is a former representative of the CUR Biology Division, and served as principal investigator on a track-1 National Science Foundation S-STEM grant.

Eric Hall is professor of exercise science and director of undergraduate research at Elon University. He is interested in the influence of undergraduate research mentorship on student and faculty development. Hall has coauthored 100 research articles, 10 book chapters, and is coeditor of one book. He has received awards for his mentorship and scholarship, including the 2022 Health Sciences Innovative Mentor Award from the Council on Undergraduate Research.

Rosalie A. Richards is associate provost for faculty development and professor of chemistry and education at Stetson University. She is responsible for the vision and strategic leadership of faculty development and support. Richards is a nationally recognized leader in undergraduate research, faculty development, STEM education, equity, and intercultural competence. She has published widely on these areas in higher education and serves frequently as a consultant to universities and other undergraduate institutions.

More Articles in this Issue

No posts found