Recommended Citation: Gunnels, Charles W., Jaclyn Chastain, Shawn Brunelle, Anna Carlin, Thomas M. Cimarusti, Mary Crone-Romanovski, Richard W. Coughlin, Carolyn Culbertson, Jason Elek, April Felton, Shawn Felton, Debra A. Giambo, Katie Johnson, Shawn Keller, Dawn Kirby, Santiago Luaces, Derek Lura, Peter Reuter, Tunde Szecsi, Rachel Tait-Ripperdan, Scott Vanselow, Judy Wynekoop, Hulya Julie Yazici, Melodie H. Eichbauer . 2024. Undergraduate Research Experiences Grow Career-Ready Transferable Skills. Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 8 (1): 15-25. https://doi.org/10.18833/spur/8/1/1

Transferable skills, namely critical thinking, communication, problem solving, and adaptability, serve as the bedrock of a successful and fulfilling career. Employers increasingly demand candidates with career-ready skills in addition to technical competencies. Therefore, institutions of higher education have increasingly fostered academic environments that couple holistic learning with career preparation (National Association of Colleges and Employers 2022). However, the ability of higher education institutions to provide students with material value has been met with increasing skepticism by graduates, employers, and society. For example, a recent report in the Chronicle of Higher Education found that only 24 percent of graduates felt that their undergraduate experience provided significant value (Kelderman 2023). In addition, perceptions about the value of higher education have become increasingly politicized in the United States (Parker 2019). In a time of public scrutiny regarding student loans, tuition, and job prospects, universities must be accountable if they wish to serve the best interests of students and society.

Undergraduate research experiences may be expected to develop career-ready transferable skills as well as, if not better than, other high-impact practices (Ashcroft, Blatti, and Jaramillo 2020; Chadha and Nicholls 2006; Hernandez et al. 2018). To promote the development of transferable skills, Florida Gulf Coast University (FGCU) implemented an institution-wide quality enhancement plan (QEP) called FGCUScholars: Think, Discover, Write in 2015 that worked with departments to integrate undergraduate research and scholarship across the university to improve students’ critical thinking, information literacy, and written communication (Gunnels et al. 2020). Although some course-embedded undergraduate research experiences (CUREs) and extensive opportunities for individual faculty-mentored research were in place before 2015, implementation of FGCUScholars started the coordinated effort to integrate research skills across the four-year curriculum and diverse majors. The transferable skills associated with FGCUScholars were identified based on an internal assessment and feedback from employers and graduate programs. Although FGCU graduates were seen as proficient in disciplinary and content knowledge, stakeholders indicated that students needed to improve their ability to (a) engage in critical thinking and complex problem solving; (b) conduct research and use evidence-based analysis; and (c) express themselves professionally through high-level writing. To enhance these skills, academic departments were required to scaffold learning competencies, from general education through capstone courses. Although academic majors were encouraged to develop research skills throughout the curriculum and students to engage in research-oriented capstones, some departments used case studies, internship and service-learning experiences, or academic reflections (in which fourth-year students gave thought to their experiences and learning over the previous four years) for their capstones. The variety of capstone formats allowed comparisons of skill levels across types.

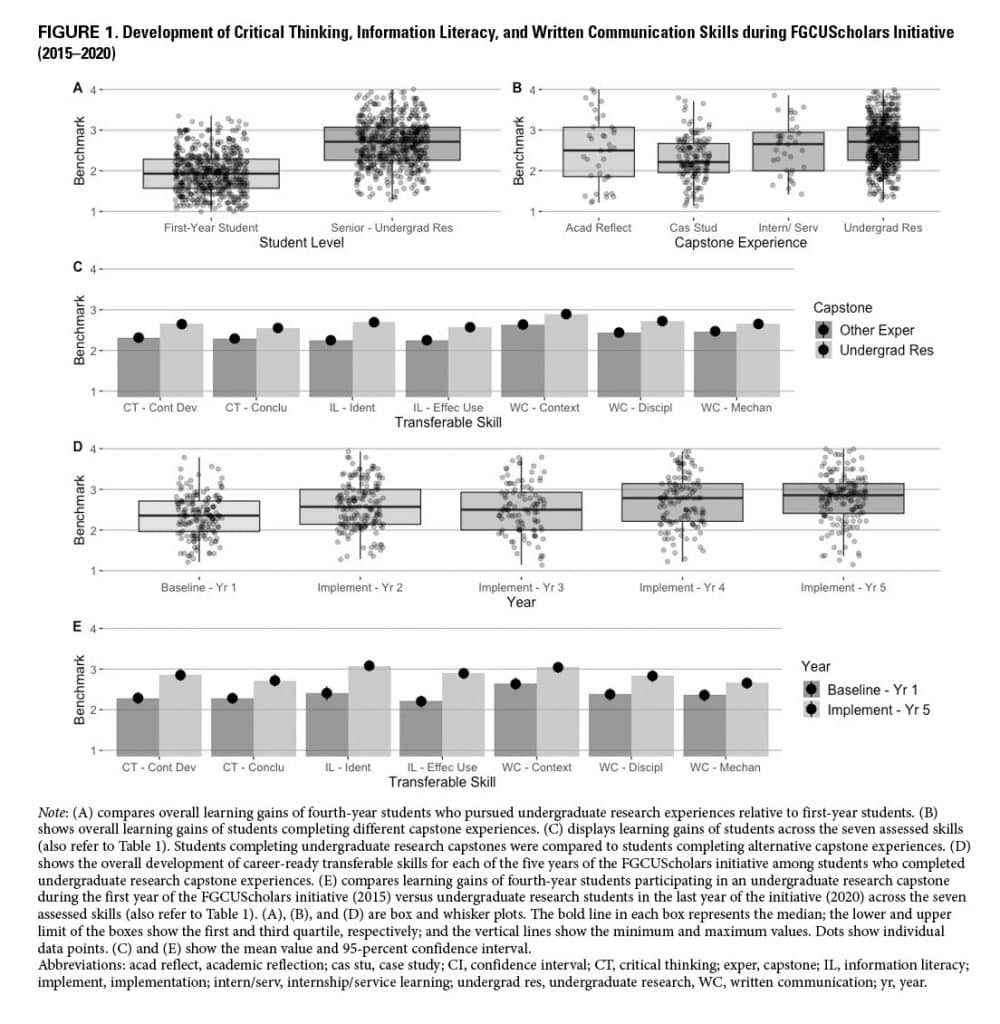

To learn how undergraduate research experiences affected the expression of transferable skills over time and relative to other learning experiences, the critical thinking, information literacy, and written communication skills of fourth-year undergraduates who participated in a research-oriented capstone were first compared with those of first-year students and then with fourth-year students who undertook different capstone experiences. If undergraduate research experiences enhanced transferable skills positively, fourth-year students who engaged in research would be expected to demonstrate higher skill levels than first-year students and fourth-year undergraduates who completed alternative capstone experiences.

Methods

FGCU, established in 1997, is a public, regional, comprehensive university serving the academic, research, and workforce needs of Southwest Florida. By 2020, the institution enrolled over 15,000 students, 85 percent of whom were undergraduates (Florida Gulf Coast University 2023). During the FGCUScholars initiative, FGCU employed about 500 full-time faculty members and offered 52 undergraduate majors, with additional graduate degrees.

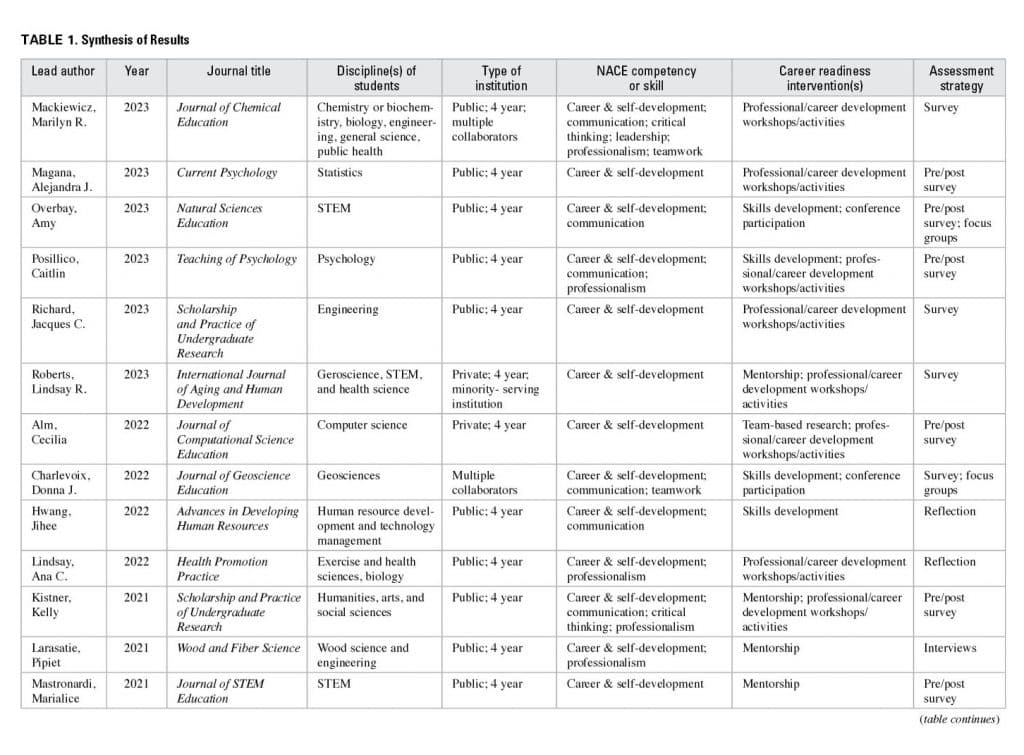

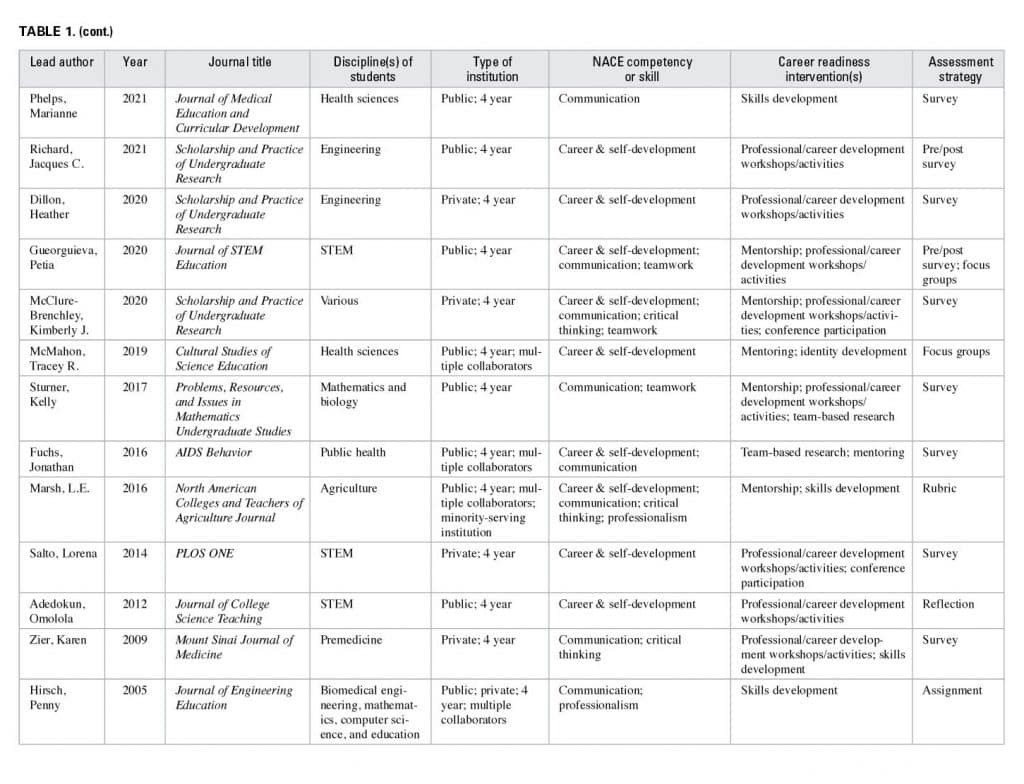

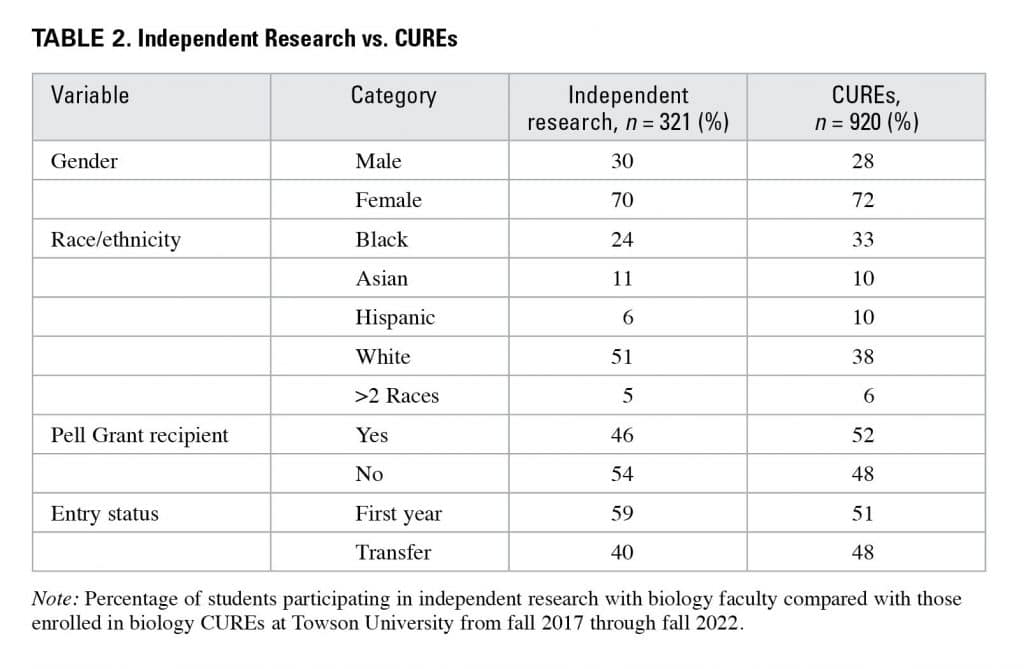

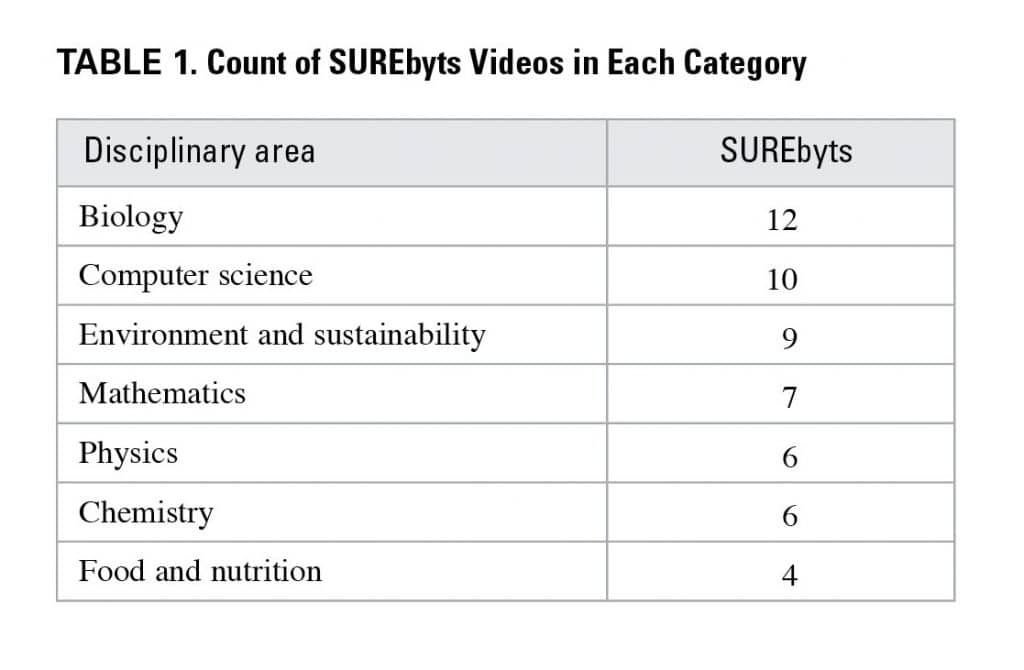

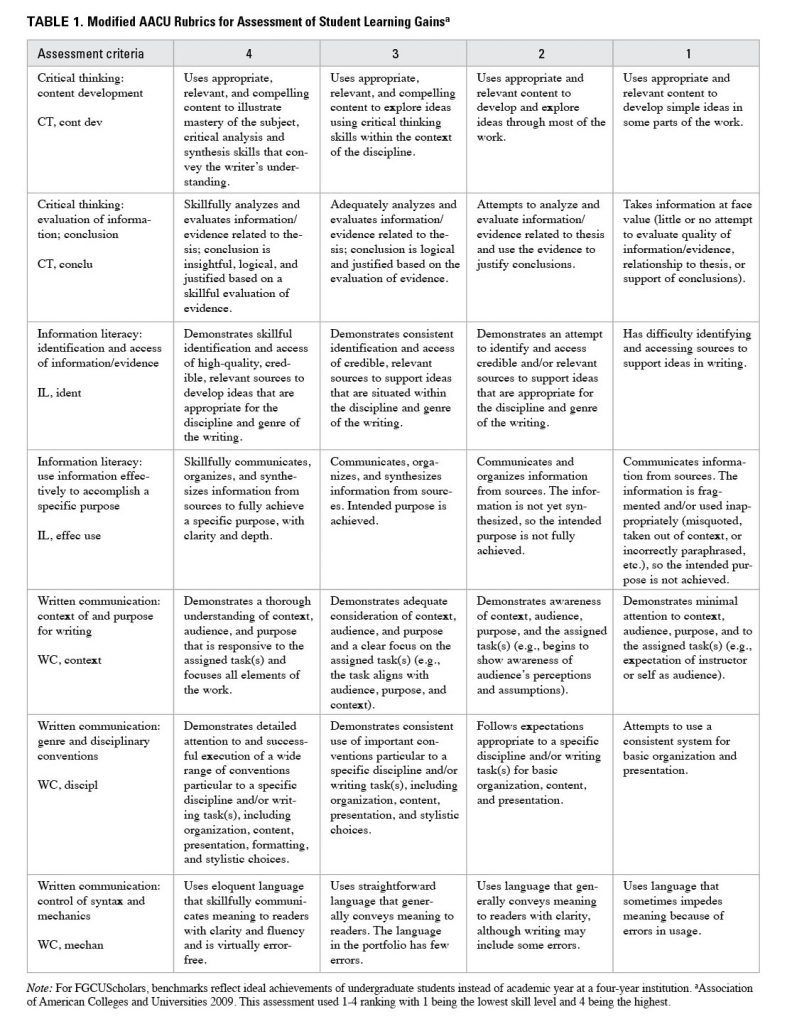

To understand how undergraduate research experiences affected career-ready transferable skills, the university conducted an annual university-wide assessment of students’ written artifacts based on seven proficiencies modified from the AACU VALUE (Validated Assessment of Undergraduate Education) rubrics (Association of American Colleges and Universities 2009). Critical thinking was assessed based on content development, analysis, and synthesis; information literacy according to students’ proper identification and effective use of evidence; and written communication by audience, disciplinary conventions, and syntax and mechanics (Table 1).

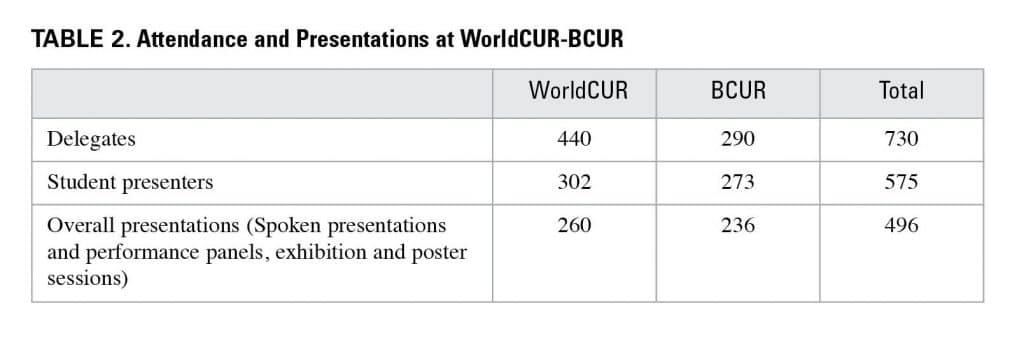

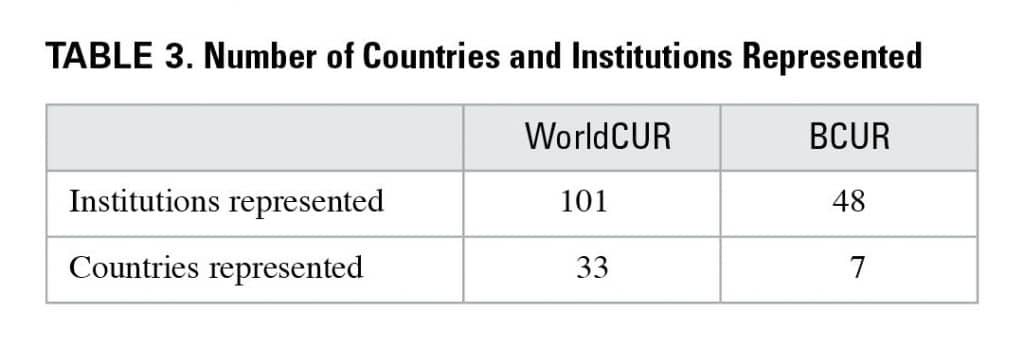

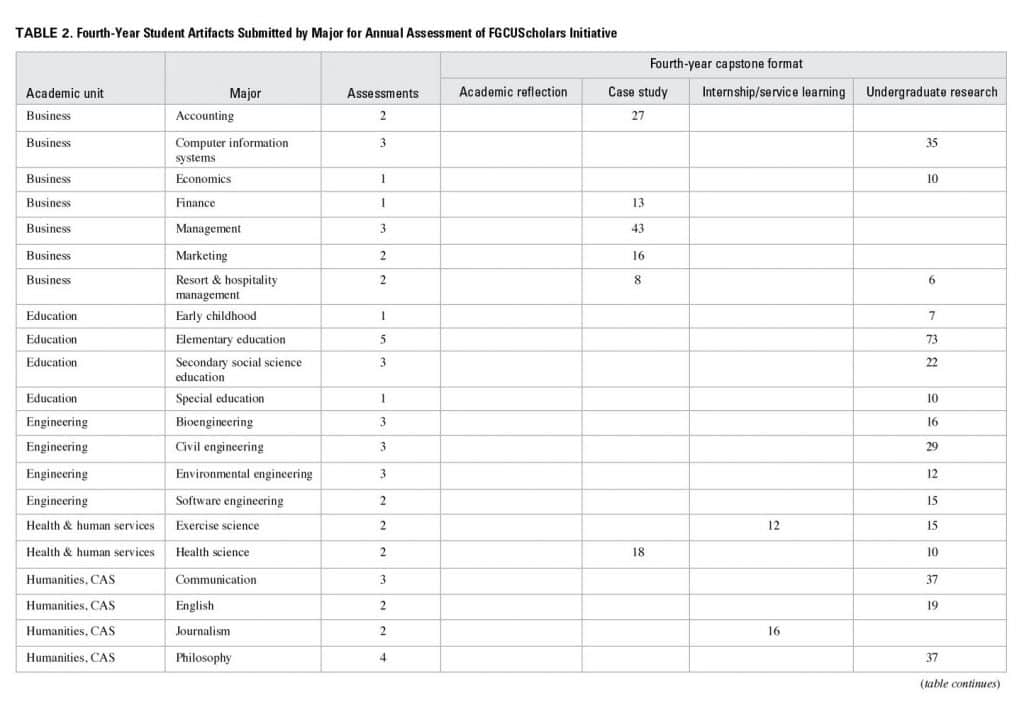

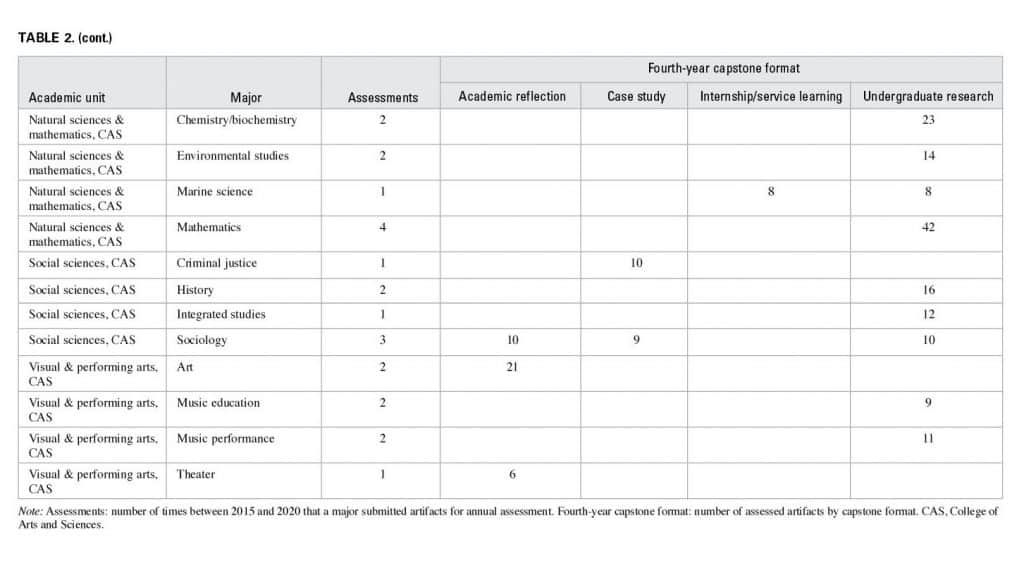

University-wide assessments took place at the end of each academic year between 2015 and 2020 (Szecsi et al. 2019). To ensure broad representation across the university, majors were organized into eight academic units that reflected disciplinary differences among the five colleges (business, education, engineering, health and human services, humanities, natural sciences and mathematics, social science, and visual and performing arts). During the spring semester, all majors were solicited to participate in the annual assessment with the goal of including at least one representative major from each academic unit (Table 2). All artifacts were assessed for majors with less than eight graduating four-year students, excluding student submissions that were set aside for norming. For larger majors, a random sample of artifacts were assessed relative to the size of the major, with a greater number of artifacts assessed from large-size majors than medium-size majors. In addition, approximately 6 percent of the final essays produced by first-year students in a second semester writing class (approximately 115 artifacts per year) were selected at random for assessment.

Faculty participation in the annual assessments was inclusive and voluntary; every assessment included multiple representatives from each of the eight academic units and the university library. The assessment began with a norming session, at which faculty agreed on the language described in the assessment rubric, learned about format differences among artifacts, gained understanding of disciplinary-specific distinctions, and worked toward conformity so that individual assessments reflected standards established by the group. Artifacts for norming were selected randomly and not assessed. Faculty then read, evaluated, and scored artifacts for each of the seven assessed criteria on a four-point scale (Table 1), with each artifact being read and evaluated by at least two assessors. A third and potentially fourth assessor were required if disagreement (< 85 percent agreement) among the first pair of assessors occurred. For each artifact, the average score was calculated for the seven assessed criteria and then a total average was computed to measure overall learning gains.

All statistical analyses were conducted with R (R Core Team 2023). Permutated analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to compare assessment results across academic levels (first-year vs. fourth-year students), capstone experiences (research, internship, case study, or academic reflection) and assessment years (years 1 to 5 of the QEP). Because permutated tests evaluate measured patterns relative to N iterations of random redistributions of the same data set, only the p value, degrees of freedom, and number of iterations that were required to resolve the p values were reported. ANOVA permutation tests with a maximum of 10,000 iterations were executed with the lmPerm package in R (Wheeler and Torchiano 2016). Significance levels were set at an alpha of .05. Visualizations of assessment results were created with the ggplot2 package (Wickham 2016).

Results

Demographics

Thirty-three of the 52 undergraduate majors submitted artifacts from their capstone during the five-year QEP (Table 2); the first-year writing program submitted assessment artifacts every year. By the final year of the QEP, artifacts from 576 first-year students and 702 graduating fourth-year students were assessed. Although the QEP focused on using undergraduate research experiences to improve transferable skills, students completed different capstone experiences depending on their major (undergraduate research, 69.1 percent, N = 485; case studies, 20.1 percent, N = 144; internship/service learning, 5.1 percent, N = 36; and academic reflection: 5.3 percent, N = 37).

Fourth-Year Students

Throughout the FGCUScholars initiative, fourth-year students who participated in undergraduate research capstone experiences showed higher-quality transferable skills in their critical thinking, information literacy, and written communication than first-year students and fourth-year students who completed alternative capstones. Fourth-year students who participated in undergraduate research showed 40.7 percent higher overall learning gains than comparable first-year students (Figure 1A, df = 1, 989; iterations = 10,000; p < .001). Moreover, fourth-year students who completed undergraduate research capstones displayed greater skill levels than fourth-year students who participated in alternative capstones (Figure 1B, df = 1, 711; iterations = 10,000; p < .001), showing on average 15.1 percent higher scores. Undergraduate research students showed the highest scores (22.6 percent) relative to students who completed case study capstones; 8.6 percent higher than students who completed academic reflections; and 2.2 percent higher than internship and service learning students. Among the assessed criteria, research students showed the highest relative scores in critical thinking (content development 14.7 percent; conclusion 11.4 percent) and information literacy (identification, 19.6 percent; effective use, 14.2 percent) compared to fourth-year students who completed alternative capstone experiences (Figure 1C).

Undergraduate Research Students

Repeated exposure to classes that integrated research skills appeared to cultivate students’ critical thinking, information literacy, and written communication. For example, research students in the fifth year of the study showed the highest overall scores (Figure 1D, df = 4, 493; iterations = 10,000; p < 0.001), scoring 21.2 percent higher than fourth-year research students in the first year of the QEP. Students in year 1 of the QEP only experienced the research-based capstone. As FGCUScholars progressed, students in the fourth and fifth years of the QEP received research skill training in their first-year writing course and in at least two additional classes within their major before the capstone. By the fifth year of FGCUScholars, graduating research students showed the highest levels in information literacy skills (identification, 27.8 percent; effective use, 30.8 percent), followed by critical thinking (content development, 24.5 percent; conclusion, 19.3 percent) and written communication skills (context; 15.6 percent; disciplinary conventions, 18.9 percent; syntax and mechanics, 12.7 percent) relative to research students who participated in only a research capstone in year 1 of the QEP (Figure 1E).

Special Cases

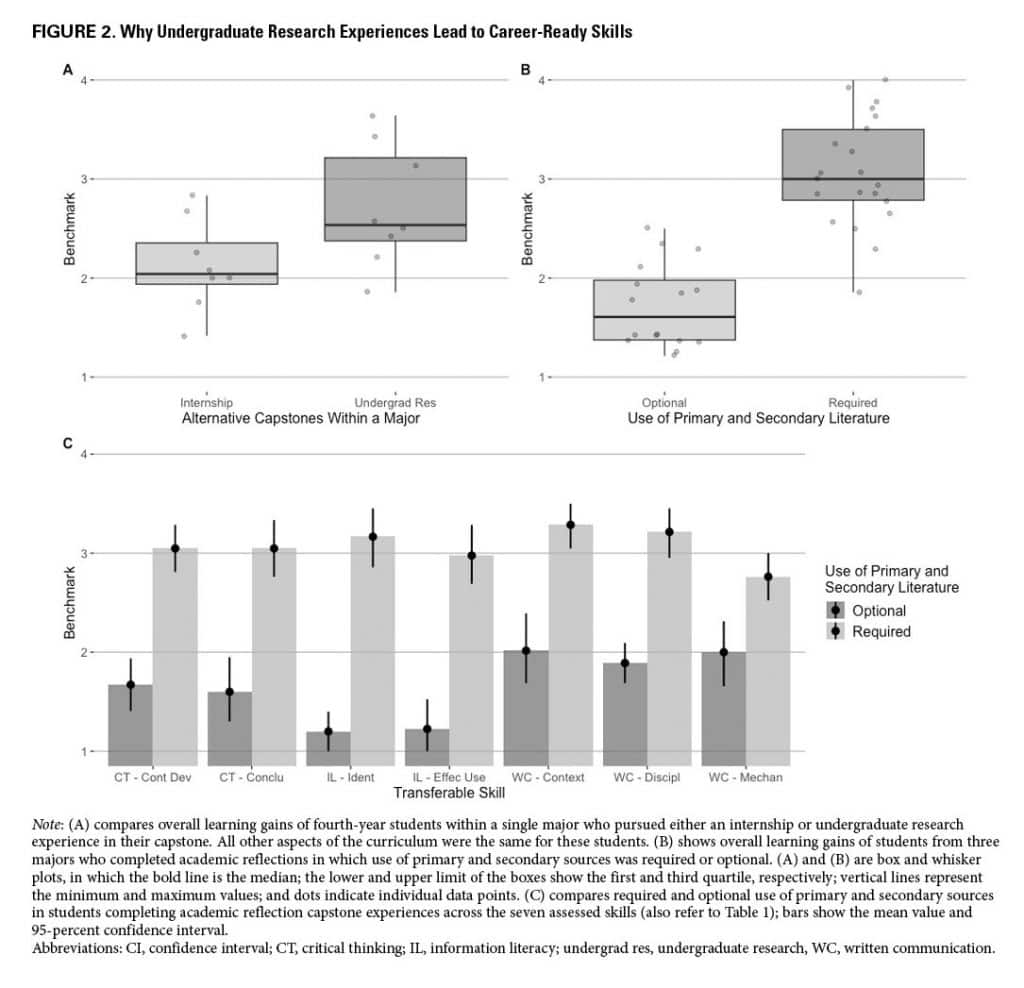

During the initiative, several cases shed light on why undergraduate research students may have shown higher career-ready transferable skills. When students completing a particular major had the choice of pursuing a research-based or internship-based capstone, research students showed higher overall skill levels than the internship students (Figure 2A, df = 1, 14; iterations = 2458; p = .039), displaying 28.1 percent higher skills. Of note, research students were required to use primary and secondary sources, which was optional for internship students. The role of information literacy was highlighted by differences among students who completed academic reflections for their capstone. In one group, the use of primary and secondary academic sources was optional (i.e., optional resource), whereas it was required for the other group. Students who completed academic reflections that required sources scored 78.2 percent higher levels than optional resource reflections (Figure 2B, df = 1, 35; iterations = 10,000; p < 0.001). Students who completed required academic reflections with sources demonstrated higher critical thinking (content development 154.2 percent; conclusion 90.6 percent) and written communication skills (context 62.9 percent; disciplinary conventions 69.8 percent; syntax and mechanics 38 percent), in addition to information literacy (identification 164.2 percent; effective use 142.3 percent) than students who produced optional resource reflections.

Discussion

FGCUScholars serves as a reminder that higher education enhances students’ overall learning and growth in ways that also support career and job readiness, with undergraduate research having a significant impact on the ability of students to utilize high-level transferable skills. These skills are vital to reflective thinking, that is, the ability to identify background assumptions and presuppositions that may influence and distort conceptions of truth and knowledge (Laursen et al. 2010; Moore and Parker 2021). Engaging in research requires students to continuously refine their hypotheses, processes, and conclusions. According to the often-cited Delphi Report, “The ideal critical thinker is habitually inquisitive, well-informed, trustful of reason, open-minded, flexible, fair-minded in evaluation, honest in facing personal biases, prudent in making judgments, willing to reconsider, clear about issues, orderly in complex matters, diligent in seeking relevant information, reasonable in the selection of criteria, focused in inquiry, and persistent in seeking results which are as precise as the subject and circumstances of inquiry permit” (Facione 1990). The results of FGCUScholars demonstrate how undergraduate research contributes to shaping critical thinkers and thoughtful communicators.

As shown in this study, pedagogies that include undergraduate research experiences build fundamental cognitive and transferable skills that students can use in their professional and personal lives. Findings of the study also showed that research-oriented transferable skills are not only associated with science and engineering, but also with social sciences, humanities, and business. For example, dialogs in these disciplines have centered on the importance of developing career-ready transferable skills in response to workforce needs (Brodhead and Rowe 2013). Beginning with first-year writing courses and continuing through capstone projects, humanities and social sciences FGCUScholars develop and reinforce skills most desired by employers throughout the curriculum (Figure 1D). Students learn to, and continually practice, thinking about problems, evaluating primary and secondary texts, and communicating findings (Figure 2B and 2C). When this was implemented across disciplines, students benefited tremendously. As shown in this study, engaging undergraduates in research is more than an apprenticeship for future scholars: it prepares the next generation of public and private sector employees to delve deeper, find new connections, and help construct a better world.

More research is required to establish long-term benefits associated with these findings. Future research should include external validation of these results, such as annual income and career advancement after graduation, as well as longitudinal assessments of individual students to confirm how these skills develop over time. Nonetheless, these results inform current debates regarding the value of an undergraduate education within the United States. Although concerns about the future of higher education persist, pronouncements of its demise and death are “greatly exaggerated.” Return on investment for education following graduation has increased (Webber 2022), and employer attitudes about higher education have improved (Flaherty and Rogowski 2021). Paying closer attention to the benefits associated with traditional higher education practices, including research-oriented undergraduate learning, can help inform national conversations about higher education that have, in recent times, relied on untested rhetoric. Supporting institutional and societal goals, undergraduate research experiences are a valuable form of experiential learning that benefit students professionally and academically, and merit further administrative support.

Data Availability

Raw data are not publicly available. Results come from annual campus-wide assessments and adhere to FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act) guidelines. Prior to analysis, the examined data were anonymized. Anonymous data can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Institutional Review Board

S2021-51 was deemed exempt, category C.F.R. 45 Part 46.104(d)(3)(i)(A).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the faculty, staff, administrators, and students at Florida Gulf Coast University who helped them make FGCUScholars such a resounding success. The authors could not have accomplished this work without their sustained support and dedication. They also wish to thank the SPUR editors and three anonymous reviewers. Their insights and suggestions made this a stronger article.

References

Ashcroft, Jared, Jillian Blatti, and Veronica Jaramillo. 2020. “Early Career Undergraduate Research As a Meaningful Academic Experience in Which Students Develop Professional Workforce Skills: A Community College Perspective.” In Integrating Professional Skills into Undergraduate Chemistry Curricula, edited by Kelly Y. Neiles, Pamela S. Mertz, and Justin Fair, 281–299. American Chemical Society. doi: 10.1021/bk-2020-1365.ch016

Association of American Colleges and Universities. 2009. “Inquiry and Analysis VALUE Rubric.” https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value-initiative/value-rubrics/value-rubrics-inquiryand-analysis

Brodhead, Richard H., and John W. Rowe. 2013. The Heart of the Matter: The Humanities and Social Sciences for a Vibrant, Competitive, and Secure Nation. Cambridge, MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Chadha, Deesha, and Gill Nicholls. 2006. “Teaching Transferable Skills to Undergraduate Engineering Students: Recognizing the Value of Embedded and Bolt-on Approaches.” International Journal of Engineering Education 22: 116–122.

Facione, Peter. 1990. “Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction.” Delphi Report. California Academic Press. https://www.qcc.cuny.edu/socialSciences/ppecorino/CT-Expert-Report.pdf

Flaherty, Thomas M., and Ronald Rogowski. 2021. “Rising Inequality as a Threat to the Liberal International Order.” International Organization 75: 495–523. doi: 10.1017/S0020818321000163

Florida Gulf Coast University (FGCU). 2023. “Headcount Enrollment, Fall 2023.” https://public.tableau.com/views/FGCU_IR_Facts_0/HeadcountEnrollment?:embed=y&:showVizHome=no&:display_count=yes

Gunnels, Charles W., Anna Carlin, Derek Lura, Judy Wynekoop, Jaclyn Chastain, Jason Elek, Katie Johnson, et al. 2020. “QEP Impact Report: FGCUScholars: Think, Discover, Write; Enhancing the Culture of Inquiry from Composition to Capstone at Florida Gulf Coast University.” Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.32592.69127

Hernandez, Paul R., Anna Woodcock, Mica Estrada, and Paul W. Schultz. 2018. “Undergraduate Research Experiences Broaden Diversity in the Scientific Workforce.” BioScience 68: 204–211.

Kelderman, Eric. 2023. “What the Public Really Thinks about Higher Education.” Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/what-the-public-really-thinks-abouthigher-education

Laursen, Sandra, Anne-Barrie B. Hunter, Elaine Seymour, Heather Thiry, and Ginger Melton. 2010. Undergraduate Research in the Sciences: Engaging Students in Real Science. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

Moore, Brooke N., and Richard Parker. 2021. Critical Thinking. 13th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE). 2022. Development and Validation of the NACE Career Readiness Competencies. https://www.naceweb.org/uploadedFiles/files/2022/resources/2022-nace-career-readiness-developmentand-validation.pdf

Parker, Kim. 2019. “The Growing Partisan Divide in Views of Higher Education.” Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/08/19/the-growing-partisandivide-in-views-of-higher-education-2

R Core Team. 2023. “The R Project for Statistical Computing.” The R Foundation. https://www.R-project.org

Szecsi, Tunde, Charles Gunnels, Jackie Greene, Vickie Johnston, and Elia Vazquez-Montilla. 2019. “Teaching and Evaluating Skills for Undergraduate Research in the Teacher Education Program.” Scholarship and Practice of Undergraduate Research 3(1): 20–29. doi: 10.18833/spur/3/1/5

Webber, Douglas. 2022. “Decomposing Changes in Higher Education: Return on Investment Over Time. FEDS Notes. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. doi: 10.17016/2380-7172.3155

Wheeler, Robert, and Marco Torchiano. 2016. “lmPerm: Permutation Tests for Linear Models.” R package version 2.1.0. doi: 10.32614/CRAN.package.lmPerm

Wickham, Hadley. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Charles W. Gunnels IV

Florida Gulf Coast University, cgunnels@fgcu.edu

Charles Gunnels is a professor and chair of biology at Florida Gulf Coast University (FGCU). He teaches animal behavior and biological statistics in R and leads study abroad trips to Caribbean and South America countries. His scientific research focuses on human-animal interactions in urban habitats. In his scholarship of teaching and learning work, he examines how undergraduate research affects student learning gains.

Jaclyn Chastain is a coordinator for academic curriculum and support at FGCU. Chastain has a psychology BA with a management minor and an MA in educational leadership with a concentration in higher education from FGCU. She has been working in higher education for the past seven years, with most of her experience relating to quality enhancement planning, student research, special student populations, and curriculum development. Chastain is currently working on her doctorate degree in education.

Shawn Brunelle is a biology masters student at FGCU. He has been with FGCU since 2013, completing his undergraduate degree in 2018. Brunelle conducts research investigating the flowering genetics of Melaleuca, while also working as an educator, teaching several biology lab courses.

Anna Carlin is an associate librarian at FGCU. At the university library, Carlin has been a subject librarian, designer of instructional materials and tutorials, and manager of media production studios. Carlin served as the information literacy leader on the development and implementation teams that steered FGCUScholars.

Thomas M. Cimarusti is a professor of music history and program coordinator for the BA degree in music at FGCU. As a recipient of numerous grants and teaching awards, Cimarusti works with undergraduate students on various research topics concerning the musical activities of the nineteenth-century religious cult, the Koreshan Unity. His students have presented papers at the National Conference of Undergraduate Research and regional meetings of the American Musicological Society.

Richard W. Coughlin is an associate professor of political science at FGCU, where he teaches courses in political theory, international relations, and comparative politics. His research focuses on Mexican and US political development.

Mary Crone-Romanovski is an associate professor in the Department of Language and Literature at FGCU, where she teaches courses in British literature and culture (1660–1830). Her current research examines representations of the material world in eighteenth-century novels by women. Her publications include articles in Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture and XVIII: New Perspectives on the Eighteenth Century as well as a book chapter in Gender and Space in Britain, 1660–1820.

Carolyn Culbertson is a professor of philosophy at FGCU. She specializes in the philosophy of language and philosophical hermeneutics. She is the author of Words Underway: Continental Philosophy of Language (Rowman and Littlefield International, 2019) and Gadamer and the Social Turn in Epistemology (SUNY Press, forthcoming).

Jason Elek teaches writing at FGCU, writes and records music, plays soccer, and kayaks through the mangrove tunnels of Southwest Florida. The rest of his time is spent chasing around his three young children.

April Felton is an assistant professor in the School of Nursing. Before entering the academy in 2019, she was a neonatal nurse practitioner. Felton teaches in the undergraduate nursing program, including child health nursing and introduction to professional nursing. Her scholarly interests include acquisition of skills by nursing students and innovative teaching practices utilizing simulation.

Shawn D. Felton is the dean in the Marieb College of Health and Human Services at FGCU. Felton returned to FGCU in August 2019 and served as the department chair of health sciences. Felton is engaged in research activities regarding musculoskeletal diagnostic ultrasound, lower extremity biomechanics and EMG activity, simulation in allied health care education, and implementation of micro-badges and digital credentials.

Debra A. Giambo is a professor of English for speakers of other languages in the College of Education. She also is an Honors Faculty Fellow, a member of the Honors Executive Board, and a Global Engagement Fellow at FGCU. Research interests include effective instructional practices for English learners, culturally responsive teacher preparation, English learner literacy, advocacy for English learners, field experience–based research, service learning and study-away experiences, and engaging undergraduate students in research.

Katie Johnson has enjoyed teaching math to others since middle school and is interested in anything that encourages more people (especially underrepresented groups) to study mathematics. She is a professor of mathematics and also coordinates the learning assistant program at FGCU. When not working, Johnson enjoys traveling, reading, cooking, yoga, and playing with her two young children.

Shawn Keller is an assistant professor in the Department of Justice Studies at FGCU. His research is in criminal justice from a biosocial perspective, examining the role epigenetics has on criminal and deviant behavior. He also pursues an interest in the use of future technologies to protect the public: facial recognition, 3D evidence presentation, 3D printing and gun control laws, body cameras with AI assistance, and use of personal and surveillance drones.

Dawn Kirby is associate provost for academic programs and curriculum development. An educator with extensive experience in teaching and administration in public and private universities, she has directed graduate dissertations, written curriculum, directed a National Writing Project site, and served in numerous administrative roles. She is a strong advocate for the value of a liberal arts education and for developing and mentoring students as leaders. Kirby has been a tenured professor since 2003.

Santiago Luaces studies wildlife biology and has a BS in biology and an MS in environmental science. His research has focused on the population ecology of the Florida burrowing owl and the effects of urbanization on their distribution. Luaces is currently working on his EDD, focusing on issues of equity in undergraduate research. He hopes to continue helping students engage in research throughout his career.

Derek Lura is dedicated to student success, which he facilitates though a combination of didactic, dialectic, hands-on, and project-based experiences. He believes that a diversity of techniques are required to teach students with different skills, mindsets, and foundational knowledge. Lura’s research focuses on prosthetic and rehabilitation devices and techniques. He also is engaged in a variety of other projects and uses research a means to facilitate engagement and learning with students outside the classroom.

Peter Reuter, retired, was an associate professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences. He loved teaching undergraduate and graduate courses and inspired students to push themselves to success when challenged. Over the last ten years, Reuter has worked with 30 undergraduate and graduate students on research projects. Students have presented posters at regional, national, and international conferences and have been coauthors of peer-reviewed articles.

Rachel Tait-Ripperdan holds master’s degrees in library and information science and in history. She is an associate liaison librarian at FGCU, specializing in teaching information literacy skills to history, language and literature, communication, and philosophy students.

Tunde Szecsi is professor and program coordinator for the elementary education program at FGCU. She holds master’s degrees in Hungarian, Russian, and English language and literature from Hungary and a PhD in early childhood education from University at Buffalo. She teaches courses in elementary and early education and English for speakers of other languages. Szecsi’s research interests include multicultural education, culturally responsive teacher preparation, humane education, and heritage language maintenance.

Scott Vanselow is an instructor in the School of Entrepreneurship at FGCU, where he teaches entrepreneurship, innovation, and computer science. He also helps to lead and train student participants in the learning assistant program at FGCU. Vanselow earned his MS in computer information systems at FGCU.

Judy Wynekoop is a professor of information systems at FGCU. Before entering academia, she worked as an internal auditor in the retail sector and as a criminal investigator for the federal government. Her research has encompassed individual and team performance in systems development and use, as well as pedagogy in information systems.

Hulya Julie Yazici is currently a full professor of analytics and supply chain management at FGCU. She received her MSc and PhD in engineering management from Missouri University of Science and Technology. She worked with the manufacturing and mining industry in North America and Europe for a decade. She has been in academia for over 30 years, with a dedicated focus on critical thinking, multidisciplinary learning, and scholarship.

Melodie Eichbauer is interim director of the Office of Scholarly Innovation and Student Research and a professor of medieval history, specializing in legal and ecclesiastical history from c. 1000 to c. 1500 CE. She works to ensure that all students have easy access to undergraduate scholarship. Eichbauer believes that research enables student scholars to shape their version of an impactful life, a life in which their scholarly experiences will make a difference in the world around them.